Python Testbench for VHDL Prototyping

We mostly do algorithm development and testing in environments with extensive library support like MATLAB and Python. When it comes to hardware implementation, questions naturally arise such as "if we make this x-bit fixed point, will the output still be accurate enough?". This is actually an vital part of algorithms development, because resource constraints can unexpectedly produce situations like: "We can't use square root here folks, reorganize the algorithm accordingly, because we don't have enough DSP slices to give the precision you want". We're not in the 90s of course, so to speak, a 20-bit multiplication operation doesn't cost a gold coin, but especially when working on FPGAs with resource utilization close to 100%, these situations do happen.

There are several ways to do these simple "FPGA-friendly" algorithm experiments ourselves, the shortest and most guaranteed way is of course to try directly in the digital design itself, i.e., at the RTL (VHDL, Verilog, ...) level. However, when test vectors are already in a Jupyter Notebook or .m script, it doesn't make sense to go and rewrite them in VHDL. In this article, I simply demonstrate this using .txt files to transport data between Python and VHDL. Even for those with access to and familiarity with professional tools like OSVVM / UVM / cocotb, I think such a "let me quickly check performance for this VHDL proto" technique is valuable. You can also think of this as a highly traceable and simple "Software-in-the-Loop" (SiL) test environment.

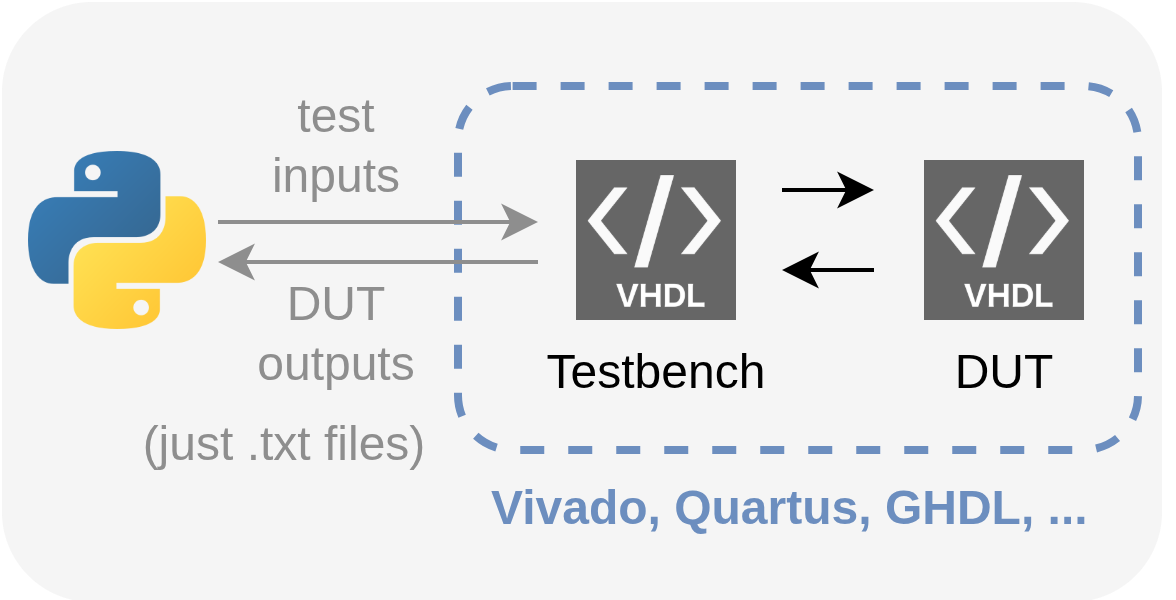

Basic Principle: Let's continue using VHDL testbenches, but let's not create test vectors in VHDL or in any professional tool. Let's keep the inputs given to the device under test (DUT) and the outputs collected from it in an intermediate format (in the simplest case, as samples line by line in .txt files). This way, we can control input-output with any language that can write and read the intermediate format, and test the VHDL prototype without leaving high-level environments like Python-MATLAB.

Method

Let's evaluate this on a simple DUT example: a single-channel, fixed-point, FIR low-pass filter that accepts 16-bit input-output. The details of the filter are not very important for this article, but you can find the source code for both it and all parts related to this example in the sobulabs/vhdl-basic-sil-fir repository. We can assume that such a filter has an entity definition like this:

entity fir is

Generic (FILTER_TAPS : integer := 19;

INPUT_WIDTH : integer := 16;

COEFF_WIDTH : integer := 16;

OUTPUT_WIDTH : integer := 16 );

Port (clk : in STD_LOGIC;

data_i : in STD_LOGIC_VECTOR (INPUT_WIDTH-1 downto 0);

data_o : out STD_LOGIC_VECTOR (OUTPUT_WIDTH-1 downto 0) );

end fir;

Let's say our VHDL testbench that will communicate with Python through .txt files connects to this entity as data_i <= data_in and data_o <= data_out. Assuming a constant sampling frequency, let's assume that the inputs needed to test this filter will be generated on the Python side as a 1D real-valued vector and written to a text file. For example, a simple chirp generation could be as follows:

import numpy as np

from scipy.signal import chirp

# File paths

input_file = "./Filter_input.txt"

output_file = "./Filter_output.txt"

tcl_script = "./run_tb.tcl"

vivado_path = "/home/buraksoner/Tools/Xilinx/Vivado/2023.2/bin/vivado" # Replace with your Vivado installation path

def generate_q_chirp(startfreq_hz, stopfreq_hz, clockfreq_hz, t_stop_ns, bitwidth, method="linear"):

num_pts = int(t_stop_ns/(1e9/clockfreq_hz));

t = np.linspace(0, t_stop_ns/1e9, num_pts) # 0=t_start. Every tick in t corresponds to one clock cycle in the testbench

x = chirp(t, f0=startfreq_hz, f1=stopfreq_hz, t1=t_stop_ns/1e9, method=method);

x_int = np.floor(2**(bitwidth-1)*x)

return x_int

def write_to_input_file(signal, file_path):

with open(file_path, "w") as file:

for value in signal:

file.write(f"{str(value.astype(np.int16))}\n")

def read_from_output_file(file_path):

with open(file_path, "r") as file:

data = file.readlines()

return [int(line.strip()) for line in data]

# Generate

clk_freq = 120e6;

t_stop_ns = 0.5e6;

chirp_start_freq_hz = 0.5e6; # our LPF has a cutoff at 3 MHz, we're sweeping from 1 to 5 to see the drop in power

chirp_stop_freq_hz = 5.5e6;

bitwidth = 16;

chirpsignal = generate_q_chirp(chirp_start_freq_hz, chirp_stop_freq_hz, clk_freq, t_stop_ns, bitwidth, method="linear")

write_to_input_file(chirpsignal, input_file)

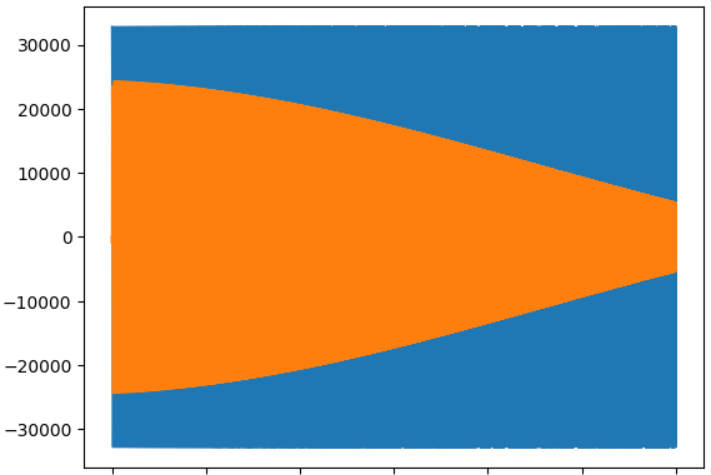

We know what should happen when this chirp is input to our FIR filter: we expect to see high amplitude at low frequencies (at the beginning of the simulation), and lower amplitude as frequency increases at later times.

Now let's look at the part of the VHDL testbench that will read Filter_input.txt and generate Filter_output.txt according to the input that passes through the DUT (to keep it short, let's skip other details of the testbench, you can look at them from the repo, this is only the part that reads the text file, feeds it to the DUT, and writes what comes from the DUT back to a text file):

...

process(clk)

file input_file : text is in INPUT_FILE_NAME;

variable input_line : line;

file output_file : text is out OUTPUT_FILE_NAME;

variable output_line : line;

variable int_input_v : integer := 0;

variable good_v : boolean;

begin

if rising_edge(clk) then

if (not endfile(input_file)) then

write(output_line, to_integer(signed(data_out)), left, 10);

writeline(output_file, output_line);

readline(input_file, input_line);

read(input_line, int_input_v, good_v);

int_input_s <= int_input_v;

else

assert (false) report "Reading operation completed!" severity failure;

end if;

data_in <= shift_right(to_signed(int_input_s, data_in'length), 0);

end if;

end process;

...

With the Filter_input.txt file generated by Python and this testbench, the DUT is now ready for simulation with the input vector. You can run this simulation on your preferred tool and obtain the Filter_output.txt file (Vivado, Quartus, GHDL, ...). In this example, I used Vivado in "batch" mode, that is, from the terminal via a TCL file, so on the Python side I was able to launch Vivado's simulator via the subprocess library and have it create Filter_output.txt.

We can also read the output as follows:

output_signal = read_from_output_file(output_file)

plt.plot(chirpsignal)

plt.plot(output_signal)

and we can observe the expected result as follows:

Discussion / Conclusion

The development-test method I introduced in this article is definitely not the most advanced method in this industry, and it's not even suitable for most large-scale projects. We have no intention of competing with methodologies like OSVVM / UVM / UVVM.

However, considering all the "entry barriers" that someone starting to work with FPGAs from scratch, students, etc., will face, it's obvious that such a simple method will be useful and "debuggable" (in the worst case, we can open and check whether the samples in the .txt file are correct!). In fact, the benefit of simplified "quick experiment" methods is actually clear even for experienced developers. When we want to quickly prototype an idea, understand how much quantization / compression loss there will be when moving to VHDL / fixed point, etc., this can be a quite fast experimentation board.

Hoping it's useful.